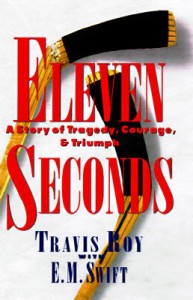

Travis Roy, a young hopeful in the world of hockey, finally realized his lifelong dream – only to see it turn, in an instant, into an unexpected nightmare. Yet for Travis another, even more unanticipated, saga was about to begin. That story, a drama of courage, determination, and the power of love, would open up an astonishing new life for one extraordinary young man – and touch the hearts of millions.

Eleven seconds was all it took. Eleven seconds to stop cold a shining career scarcely before it had take off on the ice. Travis Roy was a promising 20-year-old hockey star. Then moments into his first collegiate game as a Boston University freshman, a freak accident drove Travis into the boards. A cracked fourth vertebra left him paralyzed from the neck down.

That fateful October night in 1995 signaled the death of one dream – but also the eventual rebirth of a special kind of hope. For, though imprisoned for months in a hospital bed, then confined to a wheelchair, Travis gradually found the grit and the will to reclaim for himself a fulfilling and productive life.

From the very start of his ordeal, Travis enjoyed the support of a close-knit family; a legion of friends; his coach, Jack Parker; and his girlfriend Maija, who, despite the crippling effects of his injury never wavered in her devotion to his recovery and well-being. Ultimately, as his struggle became national news, an entire country became his fan club – cheering him on as he adjusted to daily life and rooting for him when he established the Travis Roy Foundation, which is dedicated to research and one-on-one assistance for spinal injury cases.

eleven seconds(Travis Roy’s story) is a story about America’s love affair with sports and the people who embrace its never-die spirit. Most of all, it is the story of one young man who surrendered to no limits and defied all odds, both before and after the tragedy that ended his game.

Travis has created a foundation in Boston. www.travisroyfoundation.org The Travis Roy Foundation has awarded over two million dollars in research grants towards finding a cure. Half of the money raised by the Travis Roy Foundation goes toward Quality of Life Grants to purchase adaptive equipment.

text

asdfghj

Once His Attitude About His Future Changed, Travis Roy Never Looked Back - Obituary

October 31, 2020 – E. M. Swift

Once His Attitude About His Future Changed, Travis Roy Never Looked Back

It was not until Thursday evening that I learned that Travis Roy had died earlier that day. I’d last heard from him in late July, when we commiserated by email over the cancellation of his annual wiffle ball tournament in Essex Junction, Vermont. That tourney, played in a miniature replica of Fenway Park, had raised over $6.4 million for the Travis Roy Foundation in its 19-year history. Teams come from across the country.

Despite its COVID-19 cancellation, it still raised some $365,000 in 2020, money that will go to spinal cord research and individual grants to victims of severe spinal cord injuries. That’s how loyal Travis Roy’s supporters are, how much they believe in his cause, and how much he is loved by those who knew him.

Get thoughtful commentaries and essays sent to your inbox every Sunday. Sign up now.

He finished our email exchange with this: “Would love to catch up when things settle down. Can you believe it will be 25 years this October?!”

Time had flown for Travis, even as he was confined to that wheelchair. And while the news of his passing shocked and saddened me, a voice inside me thought: He’s free now. He’s going wherever it is we all someday will be going, leaving that accursed chair behind. Free to skate like the wind, as he used to, and as he literally dreamed of doing these last 25 years. He loved those dreams. He hated to wake up from them.

Then I went back and read the “Afterward” that Travis and I added to “Eleven Seconds” in 2005, seven years after its initial publication. I hadn’t read it since we wrote it. He was 30 then. This is what he said:

“I was in Vermont when I heard the news about Christopher Reeve’s death. I listen to talk radio at night when I go to bed, and I’d forgotten to hit the snooze button. When I woke up the first thing I heard was, ‘Superman has died.’

“My first thought was: He’s finally free. He’s no longer trapped in that body. But a short time later, I heard his wife, Dana, interviewed on the Oprah Winfrey show. She said a lot of people had had that same reaction: His death was a blessing. They’d told her as much. But she didn’t feel that way at all. More importantly, Christopher hadn’t felt that way, either. From their point of view, he still had a lot of living to do. Being on a ventilator, being as restricted as he was, it’s amazing what he was able to accomplish. But right till the end, he wanted to keep doing more. And when we finally find a cure, he’ll be the first person I thank in my prayers. He carried the torch for all of us when we most needed it. He made a lot of people believe a cure was possible.”

Travis, too, still had a lot of living to do, a lot he still wanted to accomplish. He always looked forward and was planning ahead. The next fundraiser. The next motivational speech. The next reunion with his nieces and nephews. The next Boston University hockey season. He had another book in him, of that I am sure. And, of course, the scientific breakthrough he was certain would come that would get him back on his feet again.

He had come so far, overcome so much. We worked on “Eleven Seconds” most of 1996, the year after his accident, meeting every Tuesday in his dorm at Boston University. He had just returned to school, no longer as a hockey star, but as a wheelchair-bound quadriplegic who required 24-hour care. He was lonely as hell. Other students didn’t know how to react to him and shied away. Travis’ naturally gregarious, outgoing character was in a shell. He knew the old Travis was in there somewhere, but too much had changed, too many dreams had been shattered, for the old Travis to come out just yet. I was his sounding board, but I, too, was on unsure ground, off-put by the enormity of his disability. He could move his right arm a little, enough to work the joystick on his wheelchair. He could chew and swallow, but he couldn’t feed himself. He could breathe without a ventilator, but when he spoke, he did so with a gravelly voice, his vocal cords damaged by the feeding and breathing tubes that had kept him alive after his accident. And he could cry, soundlessly.

We had a deadline for the book, and when I turned in the first draft, our editor’s only critique was, “You can’t end it there. It’s too sad.”

But that’s where Travis was. We had to wait. We had to let the process unfold. Then we got a break in late March, early April 1997. The BU hockey team, which Travis should have been starring for, went on a run and qualified for the Frozen Four. Its coach, Jack Parker, was a true friend to Travis, so Travis traveled with the team. He was in the locker room before, during and after games. The team finished runner-up, much further than had been expected. Travis went to the farewell dinner. One teammate got him a beer. Another cut up his meal and fed him. It felt natural, normal, restorative to be back part of a team and be accepted as he was. His whole attitude about his future changed, and he never looked back.

Over the next 25 years, it’s incalculable how many people he’s inspired with his courage and selflessness, his speeches to students, his Ten Rules of Life. There are, of course, the spinal cord victims his Foundation has helped with grants to buy wheelchairs, build ramps, pay for therapy and home care. Travis started that Foundation when we were working on the book. But he also inspired the able-bodied to do more; to set and then re-set goals, to get back up when life struck hard. Despite all he had suffered, he felt lucky and wanted to improve the lives of the less fortunate. That was his nature. He testified multiple times before Congress and the Massachusetts State House, trying to shine a light on spinal cord research, stem cell research, government funding to speed the discovery of a cure that he firmly believed someday would come. He picked up the torch that Christopher Reeve had passed to him and carried it with passion and purpose. Travis, so charming and likeable, was a force.

He will be missed, but he, and his cause, will not be forgotten. The work of the Travis Roy Foundation will continue until one day its mission will be fulfilled. I know that in my heart.

Despite all he had suffered, he felt lucky and wanted to improve the lives of the less fortunate. That was his nature.

We didn’t talk much about religion during our times together, but he did broach the subject when we worked on that “Afterward” 15 years ago. Here’s what he said:

“In the past year or so I’ve also started to explore my faith. I’ve never been much of a churchgoer, but one of the things I’ve always wanted to do in my lifetime was to read the Bible. One of my nurses introduced me to The New Student Bible, which is more readable than the King James version. I keep it on my desk and read it often, turning the pages with my mouthstick. I’ve had fun exploring it on my own. At this point I don’t necessarily believe all the stories in it, but I’m open to learning more. I’ve heard from so many people who’ve told me they prayed for me after my accident. I always thought they were praying I’d get better and would walk again. I figured, therefore, their prayers weren’t answered. Now I’m beginning to think those people were asking for something different from God. They were asking that things would somehow come out all right for me in a larger sense. I used to think of prayers being black and white: Heal this. Cure that. Now I’m not so sure. I think maybe those prayers were answered more than I realized. And I take a great deal of comfort from that. I feel I’m getting to the point where I’m ready to surrender to God’s will, like everything’s going to be all right. That thought gives me the strength to continue to try to do my best, and whether there’s a cure for my injury or not, to move my life forward in a positive direction.”

Forward. Always forward…

He was a hero.